Cracks in walls, ceilings, and floors are among the most visible signs of building movement or material stress. While they can be unsightly, not all cracks indicate serious structural problems. The Building Research Establishment (BRE) has published detailed guidance, including BRE Digest 251 and BRE Report BR292: Cracking in Buildings, to help professionals and homeowners assess, monitor, and rectify cracking.

Property Advice Data Sheet 2:

Cracking in Buildings

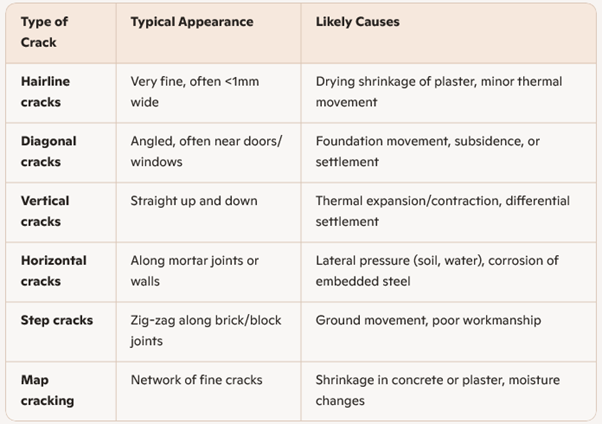

Types of Cracking

Hairline Cracks: Hairline cracks are very fine fissures, usually less than 1 mm wide, that appear in plaster, render, or paint finishes. BRE guidance notes they are typically caused by drying shrinkage, minor thermal expansion, or settlement in new buildings. These cracks are cosmetic rather than structural, and once stability is confirmed, they can be rectified with simple filling and redecorating.

Diagonal Cracks: Diagonal cracks often occur around doors and windows, running at an angle across walls. They are commonly associated with foundation movement, subsidence, or differential settlement. BRE highlights that diagonal cracking can be an early warning of structural issues, especially in clay soils or where nearby trees affect moisture levels. Monitoring is essential to determine whether the cracks are widening, which may indicate ongoing ground movement

Vertical Cracks: Vertical cracks run straight up and down walls and are often linked to thermal expansion and contraction or differential settlement between building sections. In masonry, they may appear where extensions join older structures. BRE guidance suggests that if vertical cracks remain narrow and stable, they are usually cosmetic, but wider or progressive cracks may require structural stitching or reinforcement.

Horizontal Cracks: Horizontal cracks are more serious, often appearing along mortar joints or across walls. They can result from lateral pressure, such as soil pushing against retaining walls, or corrosion of embedded steel causing expansion. BRE stresses that horizontal cracks should be investigated promptly, as they may indicate structural weakness. Rectification may involve reinforcement, rebuilding, or improving drainage to relieve pressure.

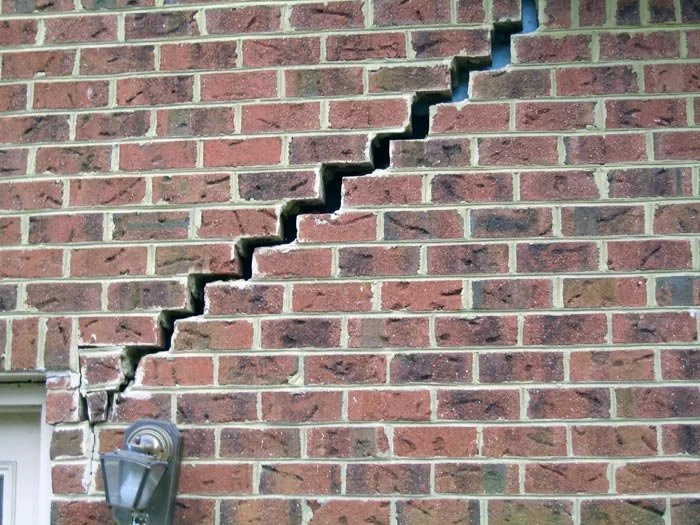

Step Cracks (Stair-Step): Step cracks follow the mortar joints in a zig-zag pattern across brick or blockwork. They are typically caused by differential settlement, subsidence, or poor workmanship. BRE guidance notes that step cracks are particularly common in areas with shrinkable clay soils. Monitoring is vital to assess whether the cracks are stable or progressive, with underpinning or rebuilding sometimes required if movement continues

Map Cracking: Map cracking appears as a network of fine, irregular cracks resembling a road map. It is usually caused by shrinkage in concrete or plaster, moisture changes, or thermal cycling. BRE guidance indicates that map cracking is generally cosmetic, though it can allow moisture ingress if left untreated. Rectification involves surface treatments, sealing, or re-rendering, combined with moisture control to prevent recurrence.

Monitoring Cracks

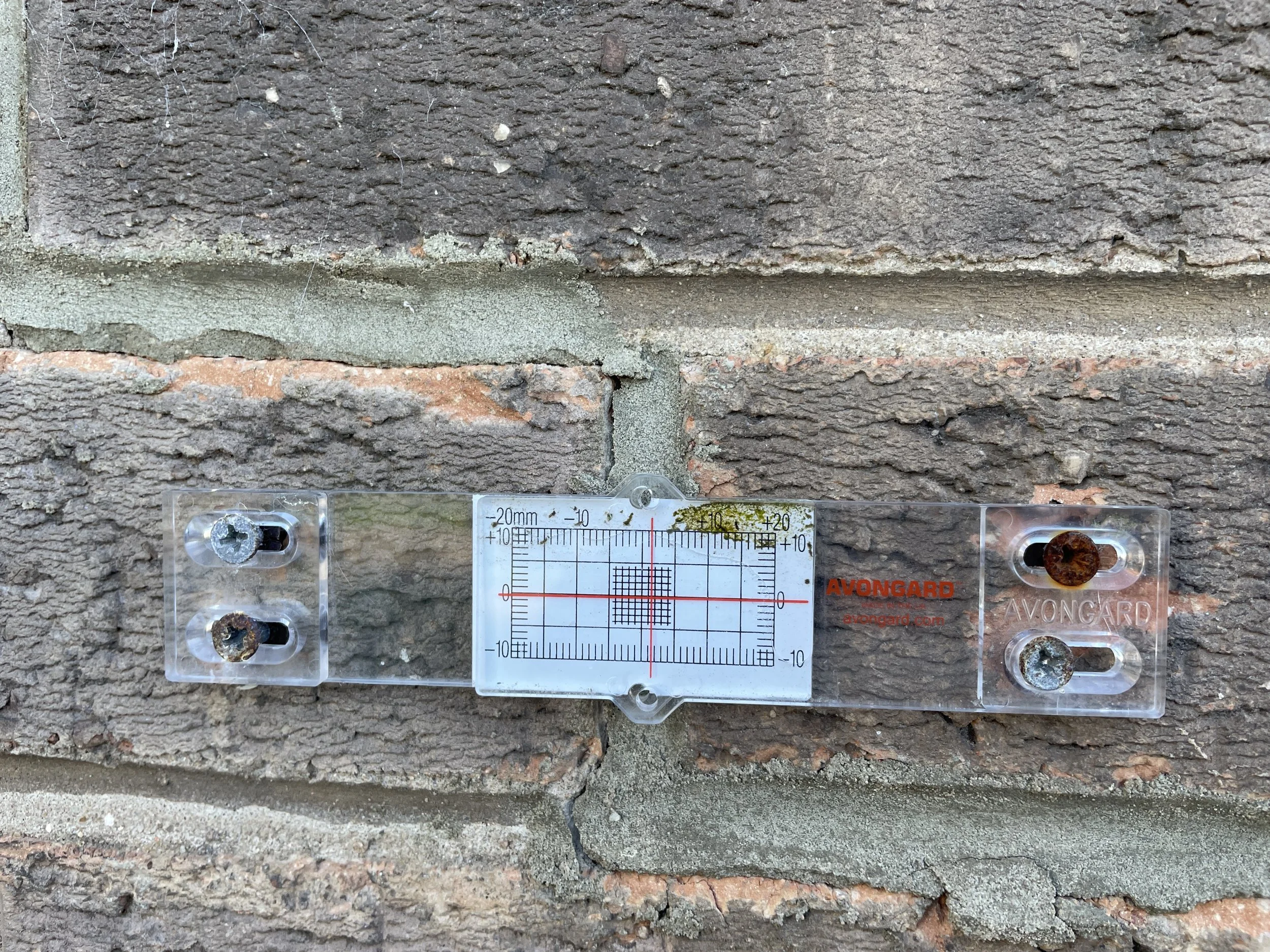

The BRE recommends systematic monitoring before deciding on repairs as this helps distinguish between cosmetic cracks (stable, non-structural) and progressive cracks (potentially structural). Monitoring can include:

Crack gauges or tell-tales to measure movement over time.

Photographic records to track progression.

Regular inspections (monthly or quarterly) to identify whether cracks are stable or worsening.

Consider environmental factors such as nearby trees, clay soils, or recent weather extremes (e.g., droughts leading to subsidence).

Once the underlying cause of cracking has been correctly diagnosed, BRE guidance emphasizes that interventions should be targeted, proportionate, and sustainable. Rectification is not simply about repairing the visible damage but about addressing the root mechanisms to prevent recurrence.

BRE Key Principle

BRE guidance consistently stresses that rectification must follow accurate diagnosis. Treating cracks as isolated defects without addressing their underlying cause—whether settlement, thermal movement, or moisture variation—will almost certainly lead to recurrence. Effective repair is therefore a two-stage process:

Investigate and monitor to confirm the cause.

Implement tailored interventions that resolve both the cause and the visible damage.

Rectification Strategies

Cosmetic Repairs

Application: Suitable for stable, non-progressive cracks such as hairline fissures caused by plaster shrinkage or minor thermal movement.

Methods: Filling with flexible fillers, re-plastering, redecorating, or applying surface coatings.

Limitations: Cosmetic work should only be undertaken once monitoring confirms stability; otherwise, repairs may quickly re-open.

Preventative Design

Application: Essential in new builds and major refurbishments to minimize future cracking.

Methods:

Incorporating movement joints in long masonry walls.

Selecting materials with compatible thermal expansion properties.

Designing foundations appropriate for soil type (e.g., deeper foundations in shrinkable clay).

Allowing for tolerances in finishes to accommodate natural movement.

Outcome: Preventative design reduces the likelihood of cracks forming and ensures long-term resilience.

Moisture Control

Application: Many cracks are linked to changes in soil moisture, water ingress, or poor drainage.

Methods:

Improving site drainage to prevent waterlogging.

Repairing leaking pipes, gutters, or roofs.

Removing or managing vegetation (e.g., large trees near foundations) that alters soil moisture.

Installing damp-proof courses or membranes where necessary.

Benefits: Moisture management not only prevents further cracking but also protects against secondary issues such as dampness and mold.

Structural Repairs

Application: Required where cracks indicate significant movement, subsidence, or loss of structural integrity.

Methods:

Underpinning foundations to stabilize subsiding soils.

Installing reinforcement such as steel bars or masonry stitching to restore continuity.

Wall ties or anchors to reconnect separated structural elements.

Rebuilding sections where damage is severe or progressive.

Considerations: Structural interventions should be designed by a qualified engineer, with BRE stressing that over-engineering can be as problematic as under-repair.

Key Take Aways

Cracking in buildings is often more about reassurance than alarm. While the sight of a crack can understandably cause concern, BRE’s structured guidance makes clear that most cracks are cosmetic and part of the natural life cycle of building materials. By applying a systematic approach—identifying the type of crack, understanding its cause, and monitoring its progression—property owners and professionals can distinguish between harmless imperfections and those that signal deeper structural issues.

The key message is that diagnosis must always precede repair. Attempting to fix cracks without addressing their root cause risks wasted effort and recurring problems. With careful observation, appropriate monitoring, and targeted rectification strategies, cracking can be managed effectively, ensuring both the safety and longevity of the building.

Ultimately, BRE’s framework empowers owners to make informed decisions: whether to simply redecorate, to monitor over time, or to seek professional intervention. This balanced perspective transforms cracking from a source of anxiety into an opportunity for proactive maintenance and improved building resilience.

Cracks are inevitable in most buildings due to material properties and environmental conditions

Diagnosis is critical: not all cracks are serious, but some may indicate subsidence or structural failure.

Monitoring first, repair second: BRE guidance emphasizes observation before intervention.

Professional advice: Engage a chartered surveyor or structural engineer for significant or unexplained cracking.

Sources: BRE Group, NHBC